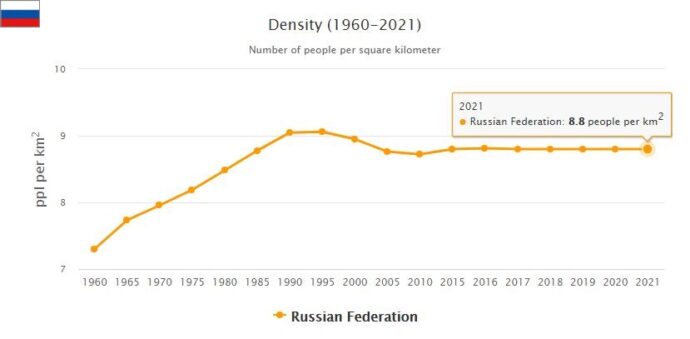

According to a 2013 census, the total population of Russia was 142,905,200 people. The population was spread across 83 federal subjects and consisted of 81.5% Russians, 3.8% Tatars, 1.4% Ukrainians and 13.2% other ethnicities such as Chechens and Bashkirs. The population density was 8 per square kilometer with the majority of people living in the western parts of the country. The largest cities in Russia were Moscow (11 million people), Saint Petersburg (4 million people), Novosibirsk (1 million people) and Yekaterinburg (1 million people). See Countryaah for more countries that also start with R.

The average age of Russians in 2013 was 38 years old with 17% aged 0-14 years old; 72% aged 15-64 years old; and 11% aged 65 or over. The median age for men was 37 years old while women had a median age of 39 years old due to higher mortality rates amongst men in Russia. Furthermore, the crude birth rate stood at 12 per 1000 while the death rate stood at 14 per 1000 reflecting a negative natural growth rate for the population. These figures indicated that without migration from other countries, Russia’s population would have been declining steadily since 2013.

In terms of religious affiliation, 75% of Russian citizens identified as Orthodox Christian while Muslims comprised 14%, Buddhists 0.5%, Catholics 0.4%, Protestants 0.2%, Jews 0.1%, other religions 1%. In addition to this, more than two thirds (67%) stated that they did not practice any religion at all indicating a high level of secularism amongst Russians in 2013.

Yearbook 2013

Russian Federation. It was another year of bloody political violence in Russia. At least 34 people were killed in two bomb attacks that followed closely in December in former Stalingrad, now Volgograd, north of the Caucasus. Suicide bombers were believed to be behind, and suspicions were directed at “Russia’s bin Laden”, the Chechen Islamist and separatist leader Doku Umarov. Earlier this year he had threatened with attacks for the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics.

According to Countryaah, President Vladimir Putin declared that terrorists would be chased and killed, and hundreds of people were arrested in the extensive police chase that followed the bombing. Particularly vulnerable were Caucasians, as Moscow still had problems with violent separatism in the North Caucasus sub-republics. The violence in Dagestan had assumed such proportions that the Kremlin replaced the leadership of the republic.

Nationalism and xenophobia gained stronger expression during the year and became a growing political force. In far-right marches, the cries were heard “dead to the Caucasians”, and in the hundreds of cities held demonstrations called the Russian march demanding “Russia for the Russians”.

In a survey, over 80% of Moscow residents wanted Central Asian and other guest workers to be deported. When a Caucasian was suspected of murdering a Russian, racist riots broke out in a Moscow suburb market in October, and a train from Tajikistan was vandalized by hooligans.

At the same time as the fear of terror in the Sochi Winter Olympics grew, President Putin seemed to want to reduce the risk of political protests. Among some 20,000 prisoners released in an amnesty in December were Russia’s three most famous prisoners: former oil company Yuko’s CEO Michail Chodorovsky and punk band Pussy Riots members Maria Aljochina and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova.

Chodorovsky had earlier this year received a ruling from the European Court of Justice, stating that the trial against him in 2005 was not fair and that he was entitled to damages. However, the European Court of Justice did not agree that he was being investigated for political reasons but considered that there were legal grounds for the tax offense. See securitypology.com for Russian arts from 1957 to 1991.

The widespread corruption seemed to increase. The chief of police forensics proposed a new police authority, which would work against the illegal transfer of capital and control the use of state resources. According to the Governor, the equivalent of nearly $ 50 billion had been illegally taken out of the country last year. This meant that one-twentieth of GDP disappeared in tax evasion, corruption or drug trafficking.

- According to AbbreviationFinder.org, Moscow is the capital city of Russia. See acronyms and abbreviations related to this capital and other major cities within this country.

Blogger Aleksey Navalnyj emerged increasingly as the leading opposition politician against President Vladimir Putin’s authoritarian regime, and his corruption revelations harmed victims. Among other things, the chairman of Parliament’s Ethics Committee was forced to resign because he did not report a valuable property he owned in the United States.

Navalnyj was charged with embezzlement from a forest company, and the trial began in April. According to Navalnyj, the prosecution was politically motivated, but in July he was sentenced to five years in prison. However, he was released on bail pending appeal and was allowed to stand in the mayor’s election in Moscow in September. Navalnyj conducted a strong regime-critical election campaign, and in opinion polls his popularity grew. But Putin-backed mayor Sergei Sobjanin won the election and, according to official data, received 51.3% of the vote while Navalnyj received just over 27%. The result was seen as a success for the opposition, but Navalnyj accused Sobjanin of electoral fraud and demanded a second round of elections. More than 900 reports of electoral fraud were made to the judiciary.

Navalnyj appealed against the verdict of embezzlement. However, it was determined, but the prison sentence was made conditional. Another charge of embezzlement was brought against Navalny, which he also saw as politically motivated.

One case that upset both inside and outside the country was the charge of tax fraud against the deceased lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, who disclosed major fraud and tax evasion among government officials. At the same time as the regime was accused of Magnitsky’s death in the 2009 arrest, a trial was opened against the deceased. The suspicions of abuse against Magnitsky in the detention were dismissed by an investigation, and instead the deceased was convicted of tax fraud in July, but without penalty.

A ban on American adoptions of Russian children became the Kremlin’s response to the so-called Magnitsky law in the US, which imposes sanctions on Russian politicians and government officials suspected of human rights abuses. Tens of thousands of people went to Moscow to demonstrate the ban on adoption.

The authorities began to apply the 2012 law aimed at voluntary organizations supported from abroad. They were considered to be engaged in political activities, were considered foreign agents and had to register as such. The tax authorities made raids, and in April the election supervisor Golos was first sentenced to fines for not registering. Golos still refused to register as a foreign agent and was banned from operating for six months in June.

In April, the lower house voted for a scandal, which sharpened the sentence to three years in prison or high fines for violating religious sentiments. It was also adopted by the upper house and signed by President Putin in June. Then Putin also signed another law that tightened the penalty for what is called propaganda for homosexuality among minors. The law led to demonstrations and international protests.

Large demonstrations were held in June in Moscow demanding the release of the 18 people charged with mass riots and violence against the police during the regime-critical protests on the Bolotna Square in 2012. According to the accused, it was the police who provoked the violence, but the judiciary put considerable resources into to prosecute, according to assessors, to deter regime-critical protests. One person was previously sentenced to prison, and in October, Michail Kosenko was sentenced to psychiatric forcible treatment indefinitely.

In July, the mayor of Yaroslavl was arrested and charged with corruption. He had previously belonged to President Putin’s support party United Russia but broke with it and won the mayor’s election in the city as an independent candidate.

The Kremlin ended up in a series of foreign political and diplomatic conflicts during the year, such as when US former security agent Edward Snowden landed in Moscow in June and sought political asylum. He was wanted by the United States for leaked top secret documents on the US security agency NSA’s surveillance. Snowden was allowed to stay, which upset the US and President Barack Obama, who canceled a planned official meeting with President Putin.

At the same time, Moscow and Washington came to terms with the civil war in Syria. The US renounced its plans to bomb a bomb in Syria following the use of chemical weapons there and agreed to the Russian proposal that Syria’s nuclear weapons should be discontinued under international control. The Russian and US foreign ministers then continued to negotiate jointly with Iran on limiting the Iranian nuclear program.

Moscow’s relations with the EU deteriorated during the year. The Kremlin was challenged by the EU’s plans to conclude association and free trade agreements with Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. Instead, the Kremlin wanted to join the former Soviet republics in a customs union with the Russian Federation, Kazakhstan and Belarus and subjected neighboring countries to political, trade and energy pressures.

Armenia fell into disrepute and announced in September that it would choose the Russian-led customs union instead of an agreement with the EU, which led to harsh criticism of Moscow from Brussels. Moldova resisted Russian pressure despite import stops for Moldovan wine and water and threats of more expensive gas. Ukraine ended up in a fierce power struggle between Moscow and the EU, where Kiev finally refused to sign an agreement with the EU at the Union summit in Vilnius in November. It led to giant protests and violence in the Ukrainian capital, and the EU accused Moscow of acting threateningly against Ukraine.

The Kremlin also put pressure on Lithuania, which was linked to Lithuania’s role as EU President, emphasizing agreements with the former Soviet republics. Among other things, imports of Lithuanian dairy products were stopped.

A more unexpected conflict came with Belarus, where cooperation on the export of potassium carbonate (potash) was broken by the Russian company Uralkali. Belarus responded by arresting Uralkali’s CEO, visiting Minsk, and accusing him of abuse of power. Moscow, in turn, decided to stop the import of pigs and pork from Belarus and reduce the supply of oil there. After the ownership of Uralkali had changed, Belarus released Uralkali’s CEO, who was then prosecuted for abuse of power also by Russian prosecutors.

Poor harvest and weak demand for Russian exports contributed to lower growth in the economy than expected. The country’s GDP was expected to grow by only about 1.5% during the year.